July 23

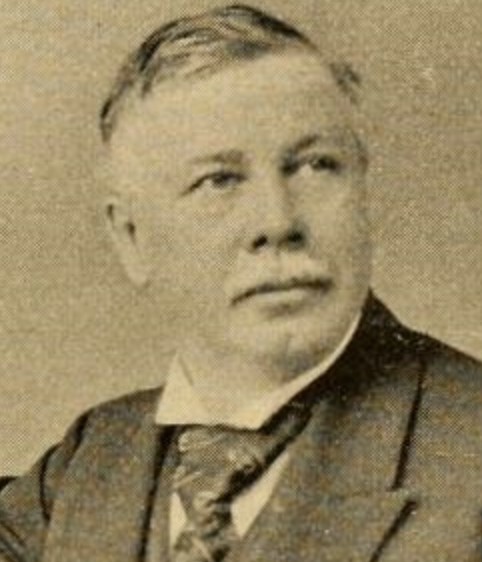

Samuel Porter Putnam

On this date in 1838, Samuel Porter Putnam, the son of a Congregationalist minister, was born in New Hampshire. He became a student at Dartmouth in 1858 and enlisted as a private in the Civil War, where, after two years of service he was promoted to captain. He became a Congregationalist minister in 1868 after three years at the Chicago Theological Seminary. Three years later he broke with that denomination and joined the Unitarians. After serving in various congregations, he then “gave up all relations whatsoever with the Christian religion, and became an open and avowed Freethinker,” as he recorded in his 1894 opus Four Hundred Years of Freethought.

During the Rutherford B. Hayes administration he was appointed to the Civil Service. He left that work in 1887 to head the American Secular Union. He was elected president of the California State Liberal Union in 1891 and the Freethought Federation of America in 1892. He noted that he visited all but four of the states and territories in his work for freethought, traveling more than 100,000 miles. His other writings include: Prometheus, Gottlieb: His Life, Golden Throne, Waifs and Wanderings, Ingersoll and Jesus, Why Don’t He Lend a Hand? Adami and Heva, The New God, The Problem of the Universe, My Religious Experience, Religion a Curse, Religion a Disease, Religion a Life, and Pen Pictures of the World’s Fair.

Putnam’s tragic death created a mild scandal. He and a young lecturer colleague, May Collins, had been touring in Boston. They returned after dinner to the home where Collins was staying and were found dead the next morning in her room, victims of leaking gas. Although they were fully clothed, and there was no “evidence of impropriety,” the religious press attacked Putnam, disclosing that he was a divorced man with two children. D. 1896.

“The last superstition of the human mind is the superstition that religion in itself is a good thing, though it might be free from dogma. I believe, however, that the religious feeling, as feeling, is wrong, and the civilized man will have nothing to do with it”

—Putnam, "My Religious Experience" (1891)

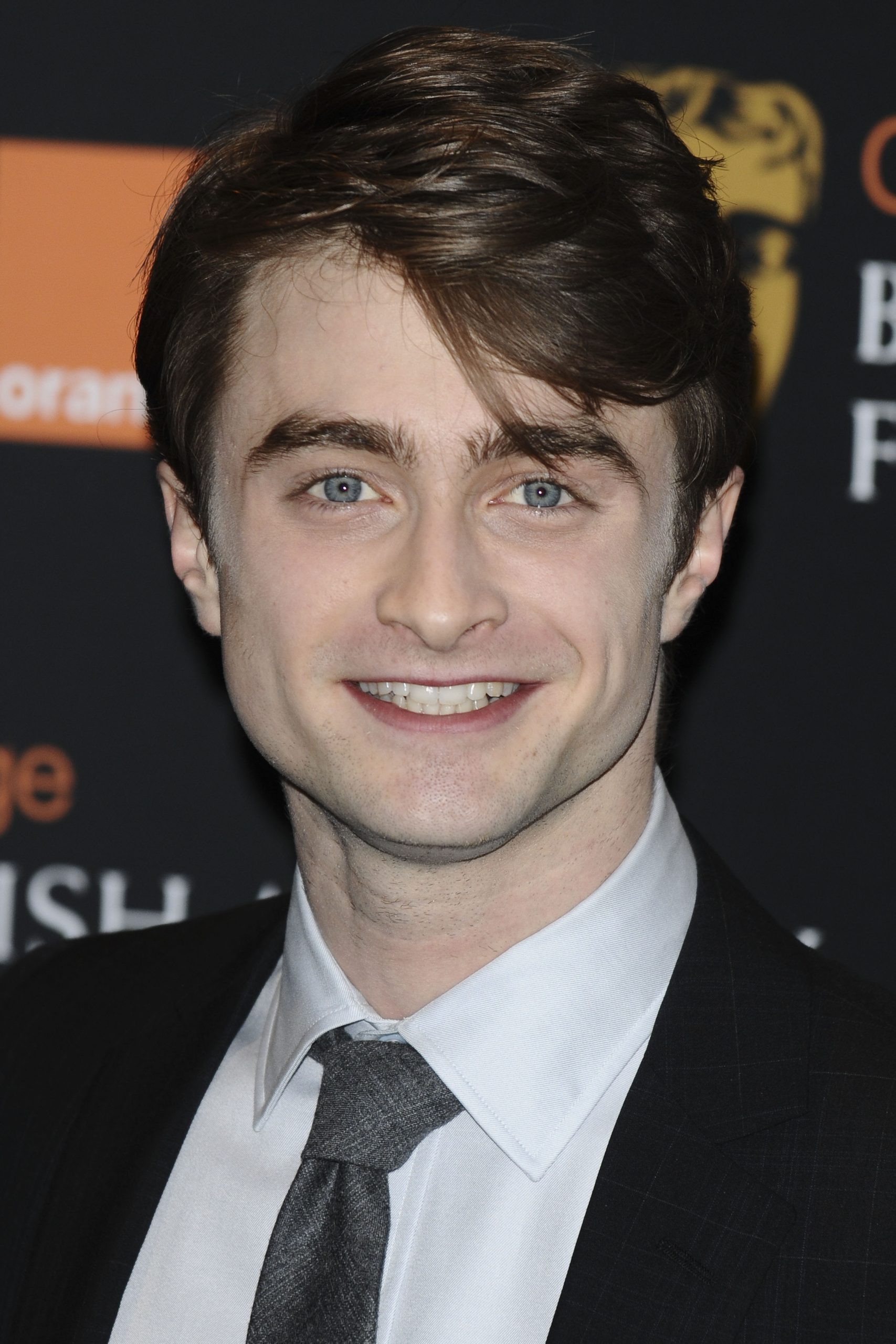

Daniel Radcliffe

On this date in 1989, actor Daniel Jacob Radcliffe was born to a Protestant father and Jewish mother in London. Radcliffe was selected for the 1999 BBC television production of “David Copperfield” to play the young title character. The film was well-received in Britain, and it helped land Radcliffe a small role in the 2001 Pierce Brosnan movie, “The Tailor of Panama.” During filming, there was a massive search in the UK to find someone to play Harry Potter in the film version of the J.K. Rowling creation. Jamie Lee Curtis, on the set of “The Tailor of Panama,” sized up Daniel Radcliffe and told his mother, “He could be Harry Potter.” Indeed, Radcliffe became immortalized as the star of the eight-movie Harry Potter series.

Radcliffe also acted in “December Boys” (2007), “My Boy Jack” (2007) and had his first theatrical role in the critically acclaimed West End play “Equus” (2007), followed by a role in the 2011 Broadway revival of “How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying.” His first non-Potter movie role was in the 2012 horror film “The Woman in Black” and was followed by other starring roles, the latest as of this writing, in 2019’s “Escape From Pretoria.” In the 2019 seven-episode series “Miracle Workers” on TBS, he played a low-level angel who answers prayers from a basement office, with Steve Buscemi playing God.

In a January 2012 interview with Parade magazine, Radcliffe said he has a problem with religion or anything else that says, “We have all the answers. … We change our minds on issues all the time. Religion leaves no room for human complexity.” He has been in a relationship since 2012 with actress Erin Darke. As of this writing, they live in London.

“I’m not religious, I’m an atheist, and a militant atheist when religion starts impacting on legislation. We need sex education in schools. Schools have to talk to kids from a young age about relationships, gay and straight.”

—Radcliffe interview, Attitude magazine (March 2012)

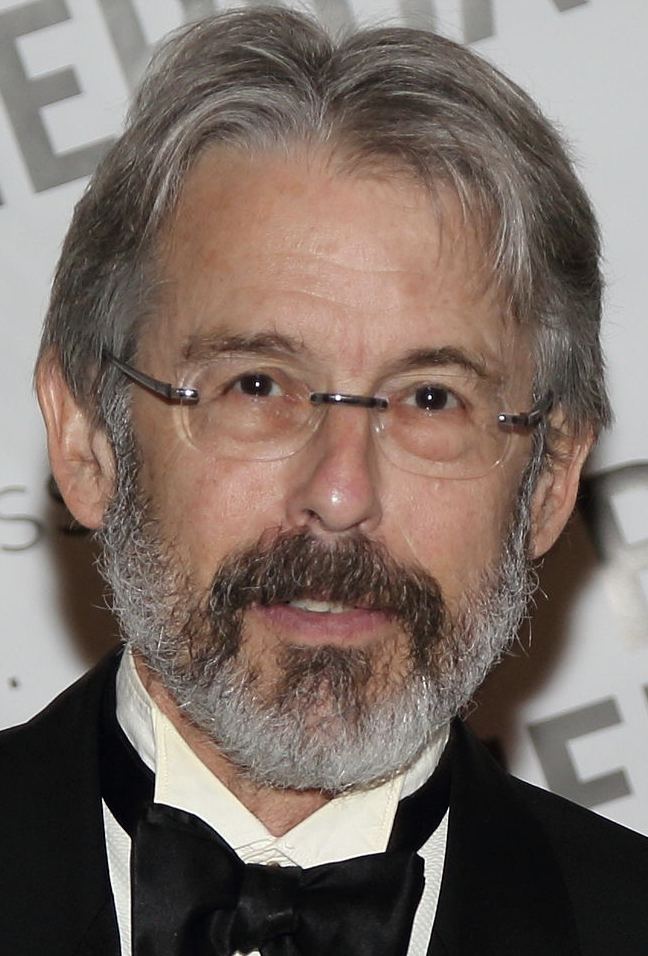

Hendrik Hertzberg

On this date in 1943, journalist Hendrik Hertzberg was born in New York City to Hazel Manross (née Whitman), a professor of history and education at Columbia University, and Sidney Hertzberg, a journalist and political activist. His father was Jewish and had become an atheist; his mother was a Quaker with a Congregationalist background. He graduated from Harvard University in 1965, where he wrote for the Harvard Crimson and became managing editor.

Shortly after graduation he started working as a reporter at the San Francisco bureau of Newsweek. During the Vietnam War he joined the U.S. Navy and was posted in New York City for two years. In 1969 he began writing for the New Yorker, a post he held until 1977. He worked as a speechwriter for Gov. Hugh Carey, then joined President Jimmy Carter’s speechwriting team and was made the head speechwriter in 1979.

Hertzberg became the editor of The New Republic in 1981 and held positions at the Institute of Politics and the Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics, and Public Policy. Hertzberg joined The New Yorker in 1992 and worked as executive director, senior editor and was the main contributor to essays on politics and society in The Talk of the Town column until 2014.

Hertzberg’s books include One Million (1970), which attempts to make large numbers less abstract, Politics: Observations and Arguments (2005), which includes discussions on the Religious Right and the importance of secularism and humanism; and ¡Obamanos! The Birth of a New Political Order (2010), which chronicles the 2008 election. Forbes named Hertzberg the seventeenth most influential liberal in the U.S. media in 2005. He is married to Virginia Cannon, a Vanity Fair and New Yorker editor. They have a son, Wolf.

Hertzberg in 2014. Photo (cropped) by Ed Lederman/PEN American Center under CC 2.0.

“The atmosphere of piety in American public life has become stifling. Where is it written that if you don’t like religion you are somehow disqualified from being a legitimate American? I’m pretty sure there is no such thing as God.”

—Hertzberg, "Politics: Observations and Arguments" (2004)

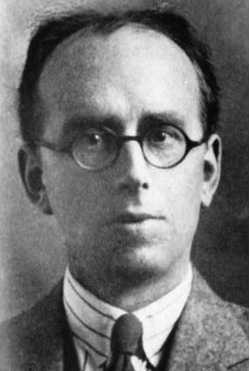

Alfred “Dilly” Knox

On this date in 1884, classics scholar and cryptographer Alfred Dillwyn “Dilly” Knox was born in Oxford, England, to Edmund Knox, an Anglican cleric and future bishop of Manchester, and Ellen (French) Knox. She died when Knox was 8. The fourth of six children, Knox was educated at Eton College and King’s College-Cambridge, where he studied classics and papyrology and was friends with Lytton Strachey and John Maynard Keynes.

When World War I broke out, he was recruited by the Royal Navy to work in its cryptology unit, which broke the code for the German “Zimmermann Note” to Mexico that helped bring the U.S. into the war. After the armistice, he completed deciphering the work of 3rd-century BCE Greek poet Herodas from papyrus fragments. He married Olive Roddam, his former secretary, in 1920. They had two sons.

He also resumed his codebreaking work, and at the start of World War II was senior cryptographer at the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park. He believed women had a greater aptitude for the work and more attention to detail than men, and thus his staff included a coterie dubbed “Dilly’s fillies.” It was here he worked with project director Alan Turing on refinement of Turing’s “bombe” device that would be instrumental in breaking encoded German “Enigma” messages and help doom the Third Reich.

Knox did not live to fully see the fruits of his labor, dying of lymphoma on Feb. 27, 1943, after working from home for an extended period due to his illness. He received the Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George for extraordinary service to the commonwealth.

At King’s College, Knox became the only confirmed atheist in his family. “According to his niece [biographer Penelope Fitzgerald], Dilly became convinced that Christianity was a two-thousand-year-old swindle eliciting false fears and hopes in believers.”

—The American Scholar, Vol. 69, No. 4 (Autumn 2000), pp. 140-42